What is digital trade?

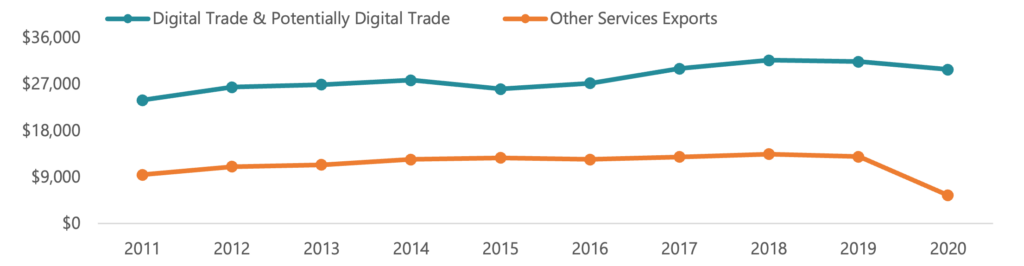

Digital trade, or e-commerce, is the delivery of products and services over the Internet.[1] Digital trade includes the exchange of end-products (e.g., downloadable movies or games), associated products (e.g., smartphones), and services that rely on or facilitate digital trade (e.g., cloud data storage).[2] Other services exports delivered via the Internet and communications networks, referred to here as “potentially digital trade,” have also contributed to rapid growth in the sector. Although gross output has been steadily growing since 2005, digital trade rapidly grew during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, increasing from $758 billion in 2019 to $941 billion in 2021. In the Northwest, digital trade values proved resilient to COVID-induced disruptions and did not experience the same precipitous drop as goods or other services exports (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Washington, Oregon, and Idaho Services Exports (2011-2020; USD millions)

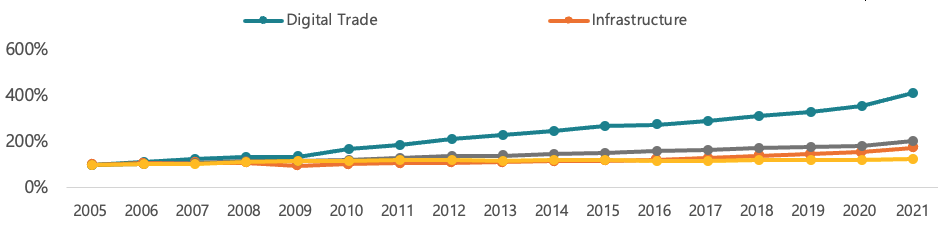

According to the Bureau of Economic Analysis, digital trade makes up more than one-fourth of the broader U.S. digital economy, which employed more than 8 million people and represented one-tenth of U.S. GDP in 2021.[3] The U.S. digital economy includes information and communication technologies (ICT) infrastructure, priced digital services, and federal nondefense digital services.[4] Digital trade is expanding faster than the rest of the digital economy, growing four-fold since 2015 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Digital Economy Gross Output, by Activity (Indexed to 2005 Levels; 100% = 2005 value)

Digital trade is more than just the classic ‘tech’ sector and is increasingly crucial for all industries, from agriculture to manufacturing. Examples in select sectors include:

Agriculture: Integrated digital trade platforms allow agricultural traders to manage the entire trade process in one place — from managing payments to tracking compliance to food safety standards — reducing the time and cost burden to participating in agrifood trade.[5]

Manufacturing: Cloud manufacturing platforms streamline the process for ordering components, allowing companies to receive instant price quotes for parts and reducing the lead time for component prototyping.[6]

How is digital trade changing?

There are many services that have the potential to be traded digitally but are not yet fully digitized. Industries, such as consulting, financial advising, and insurance services, comprise a broad category of services delivered over Internet and communication networks, yet cannot be defined as pure “digital trade.” In 2022, the U.S. exported more than $625 billion of these “potentially digital services.” Combined, these two categories represent more than $718 billion of total U.S. exports; this number will only grow as the entire global economy heads toward digitization.

The digitization of additional sectors and growth of existing digital sectors has brought much of the traditional economy into the ‘digital’ fold and been particularly beneficial to small- and medium-sized businesses and enabled these businesses to overcome barriers to entry, export their goods and services internationally, and realize the gains from global trade.[7]

How does digital trade impact the Northwest?

The Northwest is home to many of the world’s most iconic technology companies and thousands more that make and sell digitally traded goods and services. As a key part of the “West Coast Innovation Economy,” our region’s businesses are making inroads in cloud computing, big data, blockchain, and artificial intelligence. Businesses at every level and of all sizes are crucial to the Northwest’s role as a digital trade leader.

Companies such as Amazon, Intel, Micron, and Microsoft are well-known and employ tens of thousands of people in the Northwest, but the impact of the thousands of small- and medium-sized businesses is immense. A few examples include:

- Itron, near Spokane, provides intelligent metering, data collection, and utility software solutions

- Lightcast, headquartered in Moscow, Idaho, is a global leader in labor market analytics

- Eleven Software, in Portland, provides software to authenticate public wi-fi users in over 50 countries

Additionally, the impact of the gaming industry on the region is significant, with 149 companies supporting over 57,000 direct and indirect jobs and $13.5B in economic impact. Games are sold worldwide, and are almost exclusively delivered digitally[8].

The region stands to benefit from digital trade within a growing ICT sector For example, in Washington alone, exports of ICT services accounted for nearly half of Washington’s total services exports — the highest share of any state.[9] In the region, over 100,000 people are employed from digitally traded service exports.[10] Digital trade and the digital economy are and will continue to be vital to the economic well-being of the Northwest.

What could threaten the U.S. digital trade economy?

Given digital trade’s increasingly essential role in the global economy, and for Washington state specifically, emerging threats must be monitored and proactively addressed. Two of our biggest trading partners — the European Union and Canada — are both advancing digital trade policies that would disproportionately harm U.S. companies.

The E.U.’s Digital Sovereignty Plan: The E.U. Digital Sovereignty Plan aims to achieve regional technological independence by building out the European Union’s technological capabilities, which includes driving and incentivizing technological innovation, developing data best practices and norms, and imposing greater restrictions on foreign entities operating in the E.U. market.[11] In practice, such a policy would be discriminatory towards non-E.U. — and particularly, American — companies. The Plan, and similar efforts, should trigger advocacy from the United States Trade Representative (USTR) on behalf of American businesses and workers, who would be harmed by such a policy.

Canada’s Digital Services Tax: Canada’s proposed digital services tax is a yearly levy on revenue-generating activities online and if signed into law, would be retroactively effective January 1, 2022. This policy, and others like it, have been proposed to address the tax base erosion that has accompanied the rise of multinational enterprises.[12] However, this trade policy would exert uneven harm on U.S. companies and the sectors in which they are leaders and must be addressed promptly. The USTR will need to use trade tools to respond to Canada’s enactment of a DST.

WTO’s Moratorium on Customs Duties on Electronic Transmissions: Since 1988, the WTO has a moratorium in place to prohibit WTO members from imposing customs duties on electronic transmissions, such as music, e-books, films, software, and video games. It was last extended in June 2022 and is up for another extension at the WTO’s Thirteenth Ministerial Conference (MC13) in February 2024. The moratorium provides more access to digital tools and global market opportunities to sustain economies, expand education, and raise global living standards. It is especially critical to micro, small, and medium-sized businesses to access and leverage digital tools, and to sell their digital products worldwide[13]. The WTO needs to extend the moratorium at its Ministerial.

The Northwest needs digital trade. And digital trade needs the Northwest.

The Northwest is leading the nation in this increasingly foundational sector. The region’s unique innovation ecosystem — one that combines academia, private, and public sectors — will drive growth in digital trade and spread digital transformations across sectors.

A comprehensive, global digital trade strategy — rather than regional piecemeal solutions — will be necessary to capitalize on this potential and allow Washington state to continue to drive digital trade growth. A supportive tax, regulatory, and policy regime is needed to promote cooperation, foster resilience, drive innovation, and allow all to enjoy the benefits from global trade.

[1] Tripoli, Mischia, “Trade Finance and Digital Technologies: Facilitating Access to International Markets,” Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Trade Policy Briefs, No. 35. 2020, para. 5. https://www.fao.org/3/ca9941en/CA9941EN.pdf

[2] Ellström, Magnus, Emma Sandin, and Adam Reeb, “Is your digital strategy fit for the manufacturing future?” Ernst & Young, March 6, 2023, para. 16. https://www.ey.com/en_us/advanced-manufacturing/is-your-digital-strategy-fit-for-the-manufacturing-future

[3] U.S. Chamber of Commerce, “The Digital Trade Revolution: How U.S. Workers and Companies Can Benefit from a Digital Trade Agreement,” February 9, 2022, pg. 9. https://www.uschamber.com/assets/documents/Final-The-Digital-Trade-Revolution-February-2022_2022-02-09-202447_wovt.pdf

[4] https://www.theesa.com/video-game-impact-map/

[5] See note 7, pg. 10.

[6] See note 7, multiple pages

[7] Burwell, Frances and Kenneth Propp, “Digital sovereignty in practice: The EU’s push to shape the new global economy,” The Atlantic Council, November 2, 2022, para. 3. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/digital-sovereignty-in-practice-the-eus-push-to-shape-the-new-global-economy/

[8] Enahche, Cristina, “Another Digital Services Tax in Sight,” Tax Foundation, August 18, 2023, https://taxfoundation.org/blog/canada-digital-services-tax/

[9] https://www.bsa.org/files/policy-filings/01302024bsaglltrwtomora.pdf

[10] U.S. International Trade Commission, “Global Digital Trade 1: Market Opportunities and Key Foreign Trade Restrictions,” August 2017, pg. 14, para. 2. https://www.usitc.gov/publications/332/pub4716_0.pdf

[11] Congressional Research Service, “Digital Trade and U.S. Trade Policy,” December 9, 2021, para. 3. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R44565/24

[12] Highfill, Tina and Christopher Surfield, “New and Revised Statistics of the U.S. Digital Economy, 2005-2021,” November 2022, para. 1. https://www.bea.gov/system/files/2022-11/new-and-revised-statistics-of-the-us-digital-economy-2005-2021.pdf

[13] See note 3, para. 2.