“Canada, Mexico, and China are the Northwest’s top trading partners, and 40% of the jobs in Washington state are tied to trade. Tariffs will decrease Washington state’s robust exporting economy and raise prices at the grocery store. Instead, we need to establish more trade agreements that benefit all parties involved.” – Lori Otto Punke, President, WCIT

What is being proposed?

The scope is unprecedented in modern trade policy: up to 60% tariffs on all Chinese imports and potentially 20% or more imports from trading partners around the world. This would represent a fundamental restructuring of the US trade regime and a dramatic departure from decades of trade liberalization policy, including the USMCA (formerly NAFTA), which then-President Trump negotiated, that eliminates trade barriers between Canada, Mexico, and the United States.

There are also calls from Congress (the select committee on the China Communist Party) and incoming Trump administration officials, including Secretary of State nominee Marco Rubio, to revoke Permanent Normal Trade Relations (PNTR) for China (only four nations don’t have PNTR right now: North Korea, Cuba, Russia, and Belarus). The US and China negotiated an agreement and Congress agreed to grant China PNTR in 2000.[1] As a result, China must treat US goods and services as it does others, including our key trading partners and the European Union. Actions against China could enable China to favor others rather than US exports.

What History Has Shown Us

Based on historical evidence, Trump’s proposed 2025 tariffs on Canada, Mexico, and China threaten to repeat and amplify previous economic damage. Research from leading economists shows that similar 2018-2019 tariffs failed to achieve their goals while imposing significant costs on American consumers and businesses. Rather than bringing manufacturing jobs back to the U.S., companies simply relocated to other countries while retaliatory tariffs harmed American farmers and ranchers more than government programs designed to compensate them for their losses. The proposed higher tariffs could severely disrupt crucial North American supply chains, harming the communities these policies claim to protect.[2]

The Harvard Business Review wrote about the findings of these studies[2]:

While U.S. regions home to targeted industries saw no effect — positive or negative — on employment or earnings as a result of the tariffs, Chinese retaliation did harm U.S. agriculture, and that harm was only partially mitigated by government compensation.

There are a few reasons why the costs added by tariffs didn’t cause companies to move manufacturing back to the U.S., says Hanson. First, because the tariffs targeted China, importers simply moved sourcing to other countries, such as Vietnam, rather than reshoring production. Second, there weren’t U.S. factories with idle capacity that could easily replace Chinese imports. When U.S. manufacturing declined, companies didn’t just downsize their operations; they shuttered factories and laid off their workforces, so companies would largely need to invest in new facilities, rather than ramping up existing capacity.

And third, if companies were to move manufacturing out of China (or other high tariff countries), there’s no guarantee that it would return to the U.S. post-industrial cities that dominated manufacturing in the second half of the 20th century. . .

The premise of Trump’s economic policies — that manufacturing job loss has been painful for America, and especially painful for our industrial heartland — is spot on,” says Hanson. But, in terms of how to deal with that job loss, he argues, “tariffs would be pretty far down the list.”

Agriculture and Retaliatory Tariffs

In response to the 2018-2020 tariffs, “six trading partners—Canada, China, the European Union, India, Mexico, and Turkey—responded with retaliatory tariffs on a range of U.S. agricultural exports, including agricultural and food products. The agricultural products targeted for retaliation were valued at $30.4 billion in 2017, with individual product lines experiencing tariff increases ranging from 2 to 140 percent.” This resulted in an estimated $27.2B loss to American agriculture in 2018-2019. In Washington state, the reduction was up to $250 million directly, not including the reduced trade of commodities from other states through Northwest ports.[3]

Manufacturing

U.S. manufacturers often rely on imported raw materials and parts to turn into finished products. Tariffs on items like steel and aluminum have historically driven up costs for industries such as equipment manufacturing, automotive, and construction. For instance, U.S. steel users paid 9% more for steel than global competitors during the 2018 tariff period.[4] Additionally, when a country, such as China, controls the supply of critical minerals unavailable in the U.S., it poses a significant risk to manufacturers that a country will take retaliatory actions to limit the supply. For instance, many of the minerals needed for EV batteries are exclusively, or nearly exclusively, available from China.

Supply Chains

Many firms shifted operations from China to Vietnam, Indonesia, and Mexico. For example, Vietnam’s exports to the U.S. jumped 24.8% in 2019.[5] UCLA researchers found, “’bystander countries’ — those on the sidelines of the U.S.-China dispute — increased their exports of products subject to the tariffs to both the U.S. and to the rest of the world. (Exports to China were mostly unchanged.) The findings suggest that these countries didn’t just shift goods from their existing trading partners to fill a gap caused by the higher tariffs. Instead, they were able to boost production and increase exports of targeted goods into new and expanded markets. . . notably Vietnam, Thailand, Korea, and Mexico — were able to boost exports significantly, in part by providing substitutes for goods subject to the U.S.-China tariffs.”[6]

What the Impact Will Be

Household Income

For consumers, tariffs are just another form of inflation.

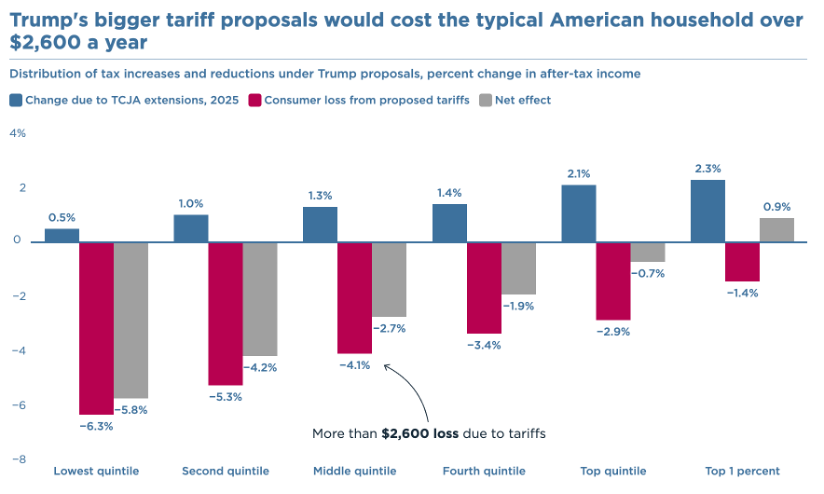

A recent analysis from the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) determined that the proposed tariffs on China, Mexico, and Canada would cost the typical U.S. Household more than $2,600/year[7], hitting the bottom-half of the income distribution even harder as a percentage of income.

Source: Peterson Institute for International Economics[7]

Macroeconomic Impact

The Tax Foundation estimates that the tariffs would reduce GDP by 0.4 percent and employment by 344,900 jobs. Retaliation could more than double the economic losses from U.S.-imposed tariffs.[8]

Retaliatory Tariffs

Imposing tariffs often leads to retaliatory measures from other countries. These retaliatory tariffs can further harm the U.S. economy by making it more difficult for U.S. exporters to sell their goods in foreign markets[9].

Ted Alden, noted trade expert and visiting professor at WWU’s College of Business and Economics, said an expected and larger risk is Canadian retaliation through its own new import tariffs, similar to what happened when the first Trump Administration imposed tariffs on steel and aluminum in 2018.[15]

Agriculture

Randy Fortenberry, an agricultural economics professor at Washington State University, said, “In a trade war, they will always focus on U.S. agriculture. That’s our surplus sector. We have already seen declines in exports to China this year, but tariffs would exacerbate that situation. It’s a tax on consumers. It’s not being explained that way at all. It’s being explained as a revenue creator and job creator. Since World War II, the U.S. economy has grown tremendously, largely because of trade.”[10]

Washington state is the top producer of apples, blueberries, hops, pears, spearmint oil, and sweet cherries in the U.S., all susceptible to retaliatory actions due to tariffs. In 2018, India imposed a 20% tariff on U.S. apples in retaliation against U.S. Section 232 steel and aluminum tariffs. Washington apple shipments to India fell 99% and growers lost hundreds of millions of dollars in exports when India finally lifted the tariff in September 2023.

U.S. dairy farmers were also hit with up to 45% retaliatory tariffs from China in 2018[11]. According to the U.S. Dairy Export Council and the National Milk Producers Federation, “Prior to the imposition of these tariffs, U.S. dairy exports to China had been experiencing robust growth, averaging 12% annually in volume and 17% in value over the previous decade. However, in 2019, following the implementation of the tariffs, U.S. dairy exports to China plummeted by more than 45% in volume and 25% in value compared to 2018. This downturn resulted in an estimated loss of $2.6 billion in U.S. dairy farm revenues from 2019 through 2021.” [12]

In addition to the direct impact on producers, demand for equipment from U.S. companies like Deere and Company falls with the decline in farm income.[13]

Cross-Border Trade with Canada

Canada is Washington state’s largest importer and the second largest export market, behind China.[14] Oil and gas are the largest import from British Columbia ($3.3B in 2023) and refined petroleum was the second largest export ($638M)[15]. This reflects the fact that crude oil comes in from Canada, is refined in Washington state, and some of that is exported back to Canada. “That’s a good example of how important it is to think about this from a supply chain relationship perspective, because if we’re tariffing what we’re importing and then we’re trying to export it again, it’s going to really mess up these markets,” said Laurie Trautman, BPRI’s director. “It’s not just something you’re skimming off the top of an import.”[15] This could also affect manufacturing jobs in Washington state.

Other state products that may make one or more cross-border roundtrips, according to various international trade resources, range from beef to equipment parts.[15]

Technology and Clean Energy

Clean technology companies employ approximately 90,000 scientists, engineers, and researchers in Washington state, and it is at the forefront of modernizing these sectors. Many clean energy and technology products manufactured in Washington state rely on materials whose supply is dominated by China. Retaliatory actions could limit or restrict the availability of these critical minerals. For example, “lithium-ion batteries used in electric vehicles rely on cobalt, graphite, lithium, and nickel, whose midstream processing (and mining in the case of graphite) is dominated by China… Advanced wind turbines depend on permanent magnets using rare earth elements, with both production and processing highly concentrated in China. Electric and hydrogen-powered vehicles also depend on these magnets in their motors, making them important in multiple sectors.” While the U.S. and its allies have made strides to nearshore or produce domestically these critical minerals, it is a multi-faceted process that will take years.[16]

Small Businesses

According to the International Trade Administration, over 12,000 small and medium-sized companies in Washington state export goods. These businesses are much less likely to be able to absorb the impact of retaliatory tariffs and non-tariff actions, especially if substitute products are available from countries not subject to the tariffs.[17]

Summary

The proposed tariffs of up to 60% on Chinese imports and 20% or more on other global trading partners would have significant adverse effects on Washington state’s trade-dependent economy, where 40% of jobs are tied to international commerce. These tariffs would effectively act as a form of inflation, costing the typical U.S. household more than $2,600 annually while potentially reducing national GDP by 0.4 percent and eliminating nearly 345,000 jobs.

Historical evidence from the 2018-2019 tariffs and other times suggest these measures would trigger retaliatory actions from key trading partners, particularly impacting Washington’s agricultural exports like apples, dairy, and cherries. The state’s clean technology sector, employing 90,000 workers, could face supply chain disruptions due to China’s dominance in critical minerals processing, and small and medium-sized businesses, which comprise over 12,000 exporters in Washington, would be particularly vulnerable to these trade barriers. Additionally, the complex cross-border relationship with Canada, Washington’s largest import partner, could be disrupted, especially in crucial sectors like petroleum refining.

References

[1] “Calls to revoke China’s trade status widen in Washington“

[2] “What the Last Trump Tariffs Did, According to Researchers“

[3] “The Economic Impacts of Retaliatory Tariffs on U.S. Agriculture“

[4] “Steel Profits Gain, but Steel Users Pay, under Trump’s Protectionism“

[5] “US – China Trade War Inspires Vietnam Growth“

[6] “Higher demand from U.S. and China means expanding into new markets“

[7] “Trump’s bigger tariff proposals would cost the typical American household over $2,600 a year“

[8] “Trump Tariffs: Tracking the Economic Impact of the Trump Trade War“

[9] “Retaliatory Tariffs Reduced U.S. States’ Exports of Agricultural Commodities“

[10] “Economists: Higher tariffs would hurt Washington farmers, consumers“

[11] “Status of Tariffs Between the United States and China“

[12] “Comments by the National Milk Producers Federation and the U.S. Dairy Export Council in the Four-Year Review of Actions Taken in the Section 301 Investigation: China’s Acts, Policies, and Practices Related to Technology Transfer, Intellectual Property, and Innovation“

[13] “Analysis-US Farmers Back Trump but Face Pain From China Tariff Threats“

[14] “WCIT Trade Dashboard“

[15] “Potential tariffs could impact annual WA imports of $7 billion from B.C.“